A self-indulgent account of my journey from ‘Vanity’ to the nature of the contemporary self

I started this blog because I was interested in understanding the history of the self. Based on the reading I’ve done so far, I can see that various academic disciplines (philosophy, sociology, critical and cultural psychology, cultural and intellectual history) have substantially different “explanations” for how and why the self has changed. I can identify explanations that seem compatible with my intuitive preconceptions (not the most objective approach, I know), but it’s clear that the underlying assumptions of any one explanation are open to legitimate criticisms — most of which I’m not even aware of.

I started this blog because I was interested in understanding the history of the self. Based on the reading I’ve done so far, I can see that various academic disciplines (philosophy, sociology, critical and cultural psychology, cultural and intellectual history) have substantially different “explanations” for how and why the self has changed. I can identify explanations that seem compatible with my intuitive preconceptions (not the most objective approach, I know), but it’s clear that the underlying assumptions of any one explanation are open to legitimate criticisms — most of which I’m not even aware of.

As a result, I hesitate. I am a complete novice with respect to this particular subject matter, and my background in these disciplines is the result of an incomplete and haphazard self-education.

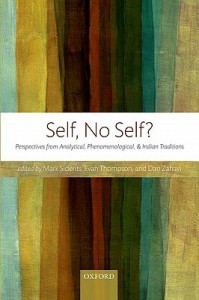

Nevertheless, I seem to have arrived at a strong preference for the explanations offered by Nikolas Rose. Many (though certainly not all) of Rose’s fundamental ideas are indebted to Foucault. I am not a student of Foucault, but — thanks to Rose — I have come to appreciate such concepts as problematization, governmentality, responsibilization (an extension by Rose of governmentality), normalization, techniques of the self, and the conduct of conduct.

I would much prefer to avoid using terms such as these in what I write. I appreciate the efficiency of communication that academic terminology provides, but unfortunately it limits one’s audience. The nature of the self is potentially of interest to anyone, not just to those who engage in academic investigation and debate. Fortunately, Rose writes with the intention of being understood by a broad audience. Read more